The UK is backing a moratorium on mining metals from the sea floor. This was, as the Guardian points out a change of plan, following a campaign from scientists and NGOs, warning the UK government of unknown consequences of deep-sea mining (DSM).

Sunak’s government joins a broad coalition wanting the International Seabed Authority (a United Nations body) to hold the line and not issue anything beyond the current exploration-only licences it has handed out. As well as the Labour Party in the UK, a variety of countries from Germany to Brazil, and a host of companies including Samsung and BMW back the same, with some, like France, looking for a permanent ban.

This for me is the mother of all cost-benefit analyses. We need a huge increase in minerals to equip not just the climate transition, but also increasing digitalisation. However, is the potential risk to an environment we know little about, worth it to build out the technologies required to halt climate change?

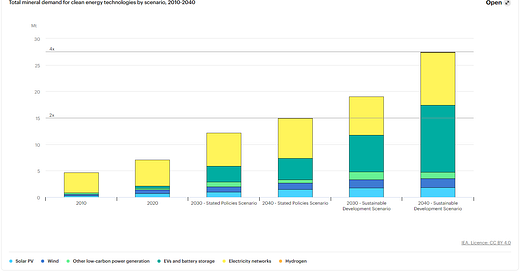

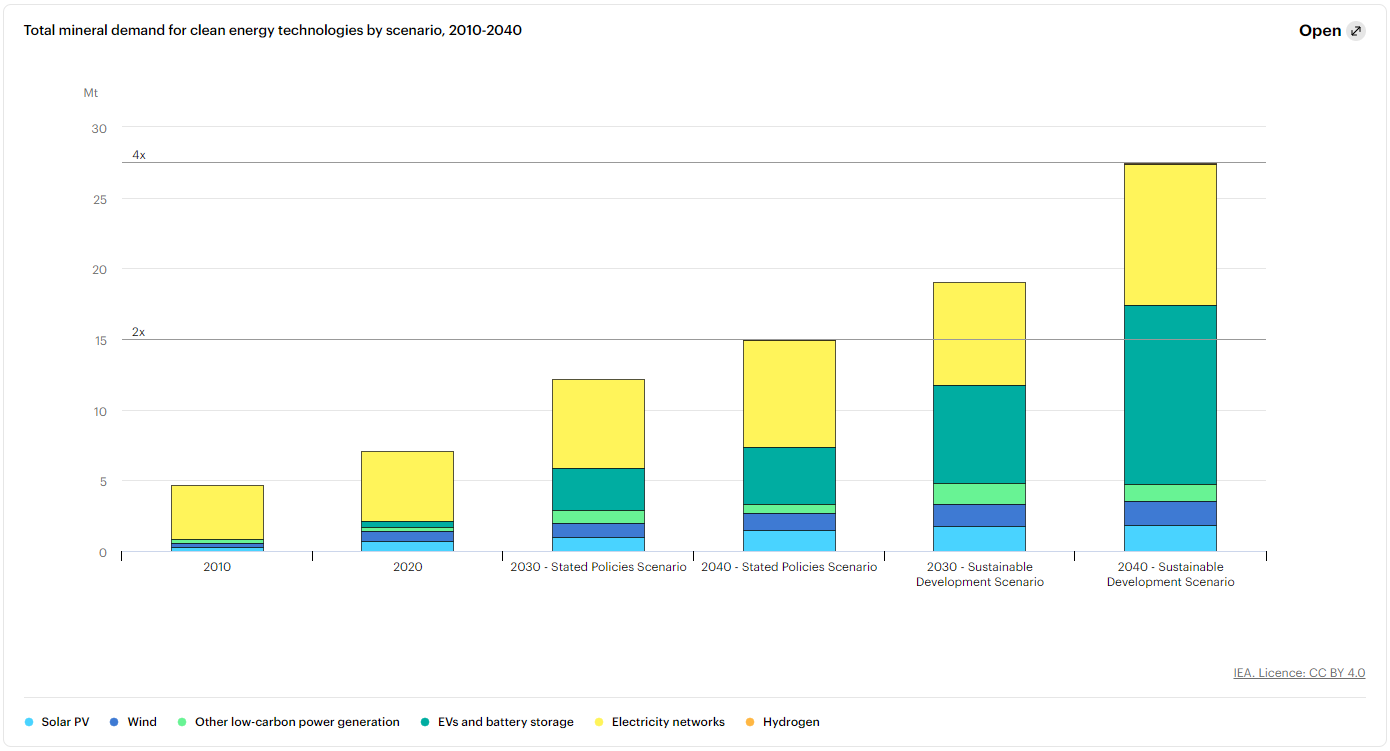

The International Energy Agency forecasts a required 300% increase in the materials required to tackle energy emissions (that’s before including e.g., heat pumps). Cabling, photovoltaic cells, batteries and the semiconductors that power the computers that run it all, all require minerals like copper, lithium and graphite. The Energy Transitions Commission has an excellent infographic on the key materials for the transition.

A slight digression - there is often an argument that this increase in minerals mining is a reason to go slow/change tact/ on net zero. It’s worth remembering how much total mining activity will decrease with decarbonisation. That is the case even when looking only at coal mining, let alone gas or oil all of which remember is underground!

The reason the deep sea is attractive is both the total volume of minerals available and the variety. The nodules (clumps of metal and rock) in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), the area most of interest to mining companies and the local sponsor country Nauru, amount to 21 billion tonnes. That is almost the total mineral demand predicted by the IEA for 2040 (a gigaton = 1 billion tonnes).

This potential volume is countered by three arguments. First, there are already enough terrestrial minerals available, second, the impacts don’t justify it, and third current demand projections don’t factor in recycling or reuse.

The increasing demand for minerals is making wider exploration and exploitation commercially viable. Lithium demand in particular is expected to grow almost 42-fold. This has driven huge discoveries recently in India and Nevada, and makes smaller deposits like in old Cornish tin mines economically attractive.

Despite these findings, much of the current global mineral wealth is predominantly in places like Indonesia or South Africa. Indonesia is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. Mining contributes substantial amounts to its economy and as such is often in direct conflict with the preservation of its flora and fauna.

Measuring biodiversity is hard. Do you go by total species, total weight of biomass, diversity or even the importance of particular species - all are important? This is what those with DSM exploration licences are attempting to understand(something that happens rarely to obtain a terrestrial licence by the way). By one measure at least the total volume of plant biomass (before counting animals), is 35 times higher for every ton mined in Sulawesi Indonesia, than in the CCZ. Others suggest an impact 25 times worse for deep-sea if you look at the area of biosphere affected. When assessing the damage of deep-sea mining, it needs to be compared to the biodiversity of mining currently not no mining at all.

The other complication is carbon release. Scientists are worried that by disturbing sediment on the sea floor, where sea life goes to die, we will release their settled carbon. This is a question of height. Does the carbon merely rise and sink again or does it enter ocean circulation and ultimately escape into the atmosphere. But when we destroy forests or disturb soil that emits significant volumes of carbon too, especially if it’s done by burning as land clearance in Indonesian forest often is.

Further impacts from light, noise or chemical pollution are all risks to the seabed, as they are on land. Startling to me though is how overlooked human rights are in this debate. Mining is one of the worst jobs available, it is back-breaking, poorly paid, and hazardous to health. While this must be weighed against the potential economic gains to individuals and countries with no alternative, we cannot overlook the individual suffering involved. DSM on the other hand will be done mostly by robots, though we know that comparable labour standards at sea in say fishing and shipping are also very poor.

As for a move to a more circular economy. I am a firm supporter of this and think there is a lot of potential growth for countries already strong in the manufacturing or processing of the original materials you’re seeking to recycle. However, I don’t see this overcoming the need for the initial build-out of transition technologies. While we need to start getting better now, the world in which we are replacing renewables from say 2040 onwards, is different to where we’re building them for the first time.

The list of countries opposing deep-sea mining surprises me because, the potential gains seem to be mostly geopolitical. Western countries are in a race to reduce their critical raw materials reliance on a small group of unfriendly countries - be that Russia for nickel, Congo for cobalt, or China for pretty much everything. The EU has an explicit strategy to increase both its domestic mining and processing to 10 per cent by 2030.

While the deep sea is regulated by the UN, it is Western companies in the strongest position to mine it. This is especially relevant for the UK, where thanks to our dinosaur stock market, a lot of mining companies are listed. This could give the UK or Brussels strong regulatory power over DSM and the ultimate destination of its outputs. The UK has form here - we have powerful laws like the Modern Slavery Act which compels companies operating in or beyond the UK to undergo due diligence along their supply chains. The obstacle however is there being sufficient mineral processing capacity in friendly countries to prepare mined products for use.. Opposition from countries like Brazil, which has both processing and deposits, makes more sense in this regard.

The argument about the impact of DSM is completely irrelevant if it is not replacing terrestrial mining. Given the increasing price of all critical minerals there is going to be a rush to produce and expand operations everywhere over the next few years. If terrestrial mining is going to expand anyway, there is simply no point taking the additional risk to the seabed.

This is where policy is vital. If DSM is proven to be less damaging, then policymakers need to find a way to wind down terrestrial mining. This could be through regulation or through raising the cost. DSM may start to put terrestrial mining out of business anyway as this paper suggests, but if there are additional penalties for biodiversity impacts (think carbon pricing/allowances but for nature), that could swing investors away from land towards the ocean. Though this will mean impacts on the economies of countries like South Africa or Indonesia - they will need support as the Just Transition Partnerships for Coal are currently trying to do.

It may be an area the UK could play a role. The mining presence of its stock market, and its leading position in renewables build-out, makes this a material interest to the country - but given its lack of own mines could be seen as more neutral than say America or Australia. Given the EU’s CRM targets, but little idea how to achieve them it’s also an area of potential bridge building with the continent. Prioritising affected countries like Chile or countries with potential mining sites like Mongolia could be part of the UK’s supposed climate diplomacy.

This debate is not going away soon, but I fear that is already proving intractable. Countries, science and environmentalists are talking part each other by using different metrics or different comparisons. Until we are operating on the same page, we may be in perennial purgatory, something that may ultimately prove to be more damaging than change.