This was written before the PM briefed he was watering down all net zero plans. If it happens that will increase both costs for Labour to reach its targets, and suck up political capital to commit to reinstating current policies. We’ll publish something in response to the speech when it happens.

Labour’s National Policy Forum came out late Friday afternoon. It promised not only to hit net zero power by 2030 but also to double down on its non-negotiable fiscal rules. There is also a guarantee to reach £28 billion of green investment a year no later than the second half of the parliament. While party figures say this delay is a consequence of their fiscal rules I’m more convinced it’s the practical reality of limited supply chains. As we explored last week, these promises are not incompatible, tweaking the pledge can help with people’s worries. Today, lets look at the fiscal rules side.

Despite being ironclad, Labour’s fiscal rules aren’t written down anywhere obvious, not having a public record of what they actually are is maybe what makes them non-negotiable. Thankfully the House of Commons library team (the country would genuinely collapse without them) has compiled a list.

In the medium term, Labour would target a current budget surplus and a falling debt-to-GDP ratio (presumably that’s around five years like government but could be longer).

Sanction borrowing only for investment providing debt is falling. That means no borrowing for day-to-day spending. HoC Library also imply this is only for infrastructure spending which as we saw last week could leave green skills programmes or consumer policies wanting. Government has a hard 3% limit on any borrowing for investment, which Labour doesn’t.

Introduce a mechanism for suspending the fiscal targets during economic shock (same as the government)

Assess public sector assets as well as liabilities, to give an overall picture of net public sector value.

So how can Labour’s climate investment pledge actually fit within these constraints? To me, there are four options.

Ditch them

Let's start by ruling out the easiest option. Fiscal rules aren’t going anywhere, yes they are imperfect, and yes they unnecessarily bind a government beyond the myriad practical constraints they already face. NIESR has much better ideas that focus on the effectiveness of policy and proper evaluation techniques. But political timelines don’t allow for this, all the justification has to be upfront, by the time a policy is seen to be effective someone else is normally in charge anyway and taking credit. Even without Starmer and Reeves's multiple iron-clad, rock-hard, steel-encased speeches, Labour’s brand wouldn’t allow them to do this. Rishi actually could, but he’d probably want the evaluation done by AI. Fiscal rules are a political tool, and as long as politicians run the Treasury we will have them in place.

Add a specific green rule

There is a surprisingly small amount of UK work on how fiscal rules can support climate spending. The most comprehensive paper comes from Brussels think-tank Bruegel ahead of the EU’s last budgetary settlement that included a major increase in green investment.

They argue that a general relaxation of fiscal rules is not targeted enough to support the transition, essentially increasing deficit risk without a guaranteed outcome. Instead, they prefer a ‘green golden rule’, that exempts climate investment from counting under fiscal rules. They prefer this to a general investment opt-out which Bruegel see as liable to be gamed and difficult to define. Given the passage of the EU green taxonomy, I don’t see how this isn’t also the case for a green get-out clause.

If we are going to have fiscal rules, then having a sizeable hole in them seems to undermine the whole endeavour. While with clear metrics markets might understand this feels like a pitfall political opponents would exploit. Fundamentally if your diagnosis of the UK’s economic problems is underinvestment, then you need fiscal conditions that allow you to address that, not just for climate.

Flex the rules

Reeves’ iron-clad suit of fiscal armour has more wiggle room than you’d think. The core tenet of Labour’s rules is to keep spending down so that debt falls. The Government’s rules, although more liberal than under Osborne, constrain borrowing both by a rolling five-year target (more sensible than a fixed one) and having a hard limit in reference to the deficit. But crucially they do that with total deficit, i.e. all government spending including capital investment.

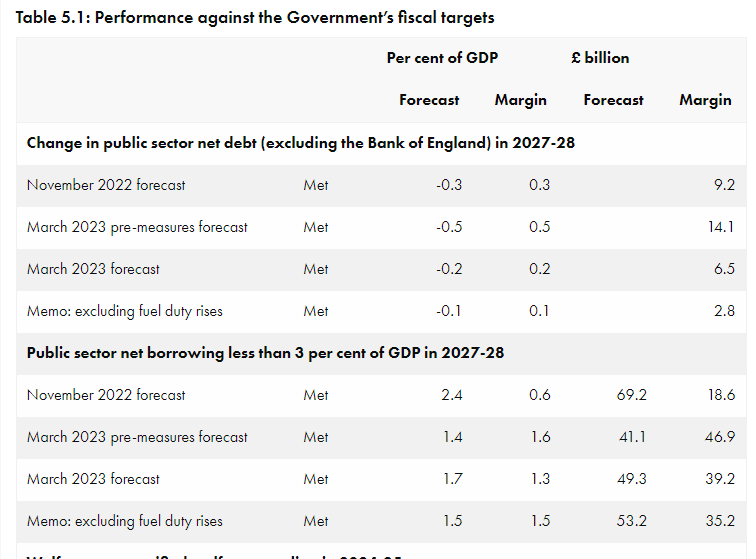

Labour could quite easily apply their fiscal rules to current deficit which does not include capital investment. This meets their pledge to allow room for investment and increases the headroom for borrowing, £39.2b according to the OBR (table 5.1) (though at the mercy of changing OBR forecasts). And remember there’s already a bit of headroom in the government's current fiscal rules, £6.5b, enough to pay for Labour’s retrofit plans.

Provided you buy the GDP boost of investment and particularly green spending, which the IMF shows are large (though there is a potential question about their permanence), then it's easy to see how you also meet the former rule. Carsten at IPPR thinks this might even be the case without flexing the rules.

estimated multipliers associated with spending on renewable and fossil fuel energy investment are comparable, and the former (1.1-1.5) are larger than the latter (0.5-0.6) with over 90 per cent probability. These findings survive several robustness checks arguing that stabilizing climate and reversing biodiversity loss are not at odds with continuing economic advances. Batini et al 2021, IMF

Given this could sound like a weakening of fiscal rules, and is likely to be painted as such by the Conservatives, I’d also bolster them with an additional rule. This has got to be controlling debt interest costs, which thanks to Liz Truss amongst others, have ballooned in recent years. According to the ONS “debt interest payable was £9.8 billion in April 2023, £3.1 billion more than April 2022 and the highest April figure since monthly records began in 1997”. Bringing in a new rule to monitor and control debt interest, would a) attach blame for higher payments to the Tories and b) show Labour is bringing unwanted costs down, freeing money for more productive uses.

Money in the (green) bank

Thanks to climate people sticking with the dry fiscal policy this far, this is where climate spending gets (more) interesting.

Labour’s pledge to count assets as well as debt is smart for a party that wants more state assets. The National Wealth Fund, GB Energy, equity or stakes in new manufacturing, all will sit on the positive side of the balance sheet. Not only could this prevent them from being sold off, but it would mean they offset the total level of debt. This focus on net wealth is made easier as ONS now publishes the data. Organisations like Resolution Foundation and IPPR think improving public sector net worth should be the main focus of fiscal rules, but I don’t think Labour could do that until maybe a second term.

There’s also a case to park a lot of climate spending off government’s balance sheet entirely. As a close friend quipped recently, say off balance sheet three times and you’ll be haunted by the ghosts of permanent secretaries until your dying days. Yet this isn’t just a way of being profligate and hoping no one notices. Germany, not normally known as a free-spending nation, has its state investment bank the KfW off its balance sheet. Norway's vast sovereign wealth fund is the same. It makes sense, these are independent organisations with their own balance sheets. Government doesn’t control that money, so it can’t do anything about it in order to meet its fiscal rules. Norway’s SWF’s value is over 3x the country's GDP, you’d have no need for fiscal rules if you could access that cash the night before a budget.

So if Labour’s plans are to spend a large proportion of its £28bn through an independent development bank or wealth fund this could be very appealing. Albanese’s government has given similar sums to its green bank the CEFC in Australia, whilst tasking it with specific objectives from its manifesto like updating the grid. That could be a great model for Labour to follow, juicing the UK Infrastructure Bank and/or turning it into the proposed National Wealth Fund (more on that in the future). The benefit of not meeting spending until later in the parliament gives you time to prep these institutions, especially UKIB has a review of its capital levels in 2025/26.

The complication for Labour is the initial funding. I’m not 100% but I think any capitalisation of UKIB/NWF by a first-term Labour Government would count as government spending. However, a bigger capital budget would allow UKIB to borrow more itself on international markets, limiting what a Labour Government would need to do.

None of these will be plain sailing. Labour's diagnosis of the economy, like Biden's, is that government needs to step up to solve problems. Old hands in the treasury will warn of jittery markets ready to give Labour the Truss treatment. But there are other pockets (notably the climate team) who would be supportive. And fundamentally if a new Labour government isn’t pushing against out-of-date HMT thinking there’s no hope.

The struggles to reduce emissions in the UK as I will say many times in this newsletter are not unique to climate. Rolling out and scaling new technology, building the right infrastructure, getting businesses to spend or encouraging knowledgeable and flexible consumers and all problems faced by the wider economy. We shouldn’t therefore be looking for solutions that support climate action, and not other issues in the UK. This would look like exceptionalism and could undermine Labour’s entire efforts to look responsible. Thankfully there is plenty of room within Labour’s current commitments to do that.

Takeaways

Not hitting £28 billion a year until mid-parliament isn’t a consequence of Labour’s fiscal rules, but the fact that it takes time to increase spending and supply chains are currently limited.

The party won’t ditch its fiscal rules, but there is room to flex them. Measuring against current deficit not total, while adding a debt interest rule and monitoring national wealth will all maintain fiscal responsibility and allow Labour to increase public investment,

Giving more capital to independent green banks like Norway, Germany or Australia could also ease budget constraints.