EE#30 Planning for the worst

Playing by the rules only gets Labour so far, it’ll need an escape valve

Government wants things built, fast. Labour’s economic theory is that the UK is a low-investment country and that higher investment will mean higher growth. Labour is a political party, not an academic economist. It wants to make new investment real to voters. Skills and innovation are massively important, but not that visible. Building infrastructure is the political manifestation of higher investment. Whether houses, wind farms, or pylons, Labour MPs can stand outside them in hi-vis, while the public can see evidence that under a Labour government things have changed - a move away from stagnation.

The need to build more brings us to our old, creaking planning system. The issues here are well-rehearsed:

There is too great a role for organised, minority opposition to obstruct development.

Local authorities and other statutory bodies like Natural England, don’t have the resourcing required to process applications.

Even if developments follow the rules, there is ample space for discretionary decisions to refuse them.

All this means planning takes too long, development risk is too high, and investors see UK infrastructure as too risky to finance.

Labour’s forthcoming planning bill is their attempt to address these issues. There will be lots of reforms, from more regular National Policy Statements to changing thresholds and processes for Nationally Strategic Infrastructure Projects. It should include details on the proposed National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Body, and crucially, where and on what 300 new planning offers will work.

All sensible but all very much working within the current system. This makes sense. Working within the current system provides a cap on political risk. It confines opponents to local campaigns rather than a unifying national one. And, as Public First research shows a well-resourced planning system, delivering mixed-use developments, has real economic potential. But it also caps potential outcomes, especially if resource isn’t available. It mitigates the issues above but doesn’t get rid of them.

Can we really deliver the infrastructure we need?

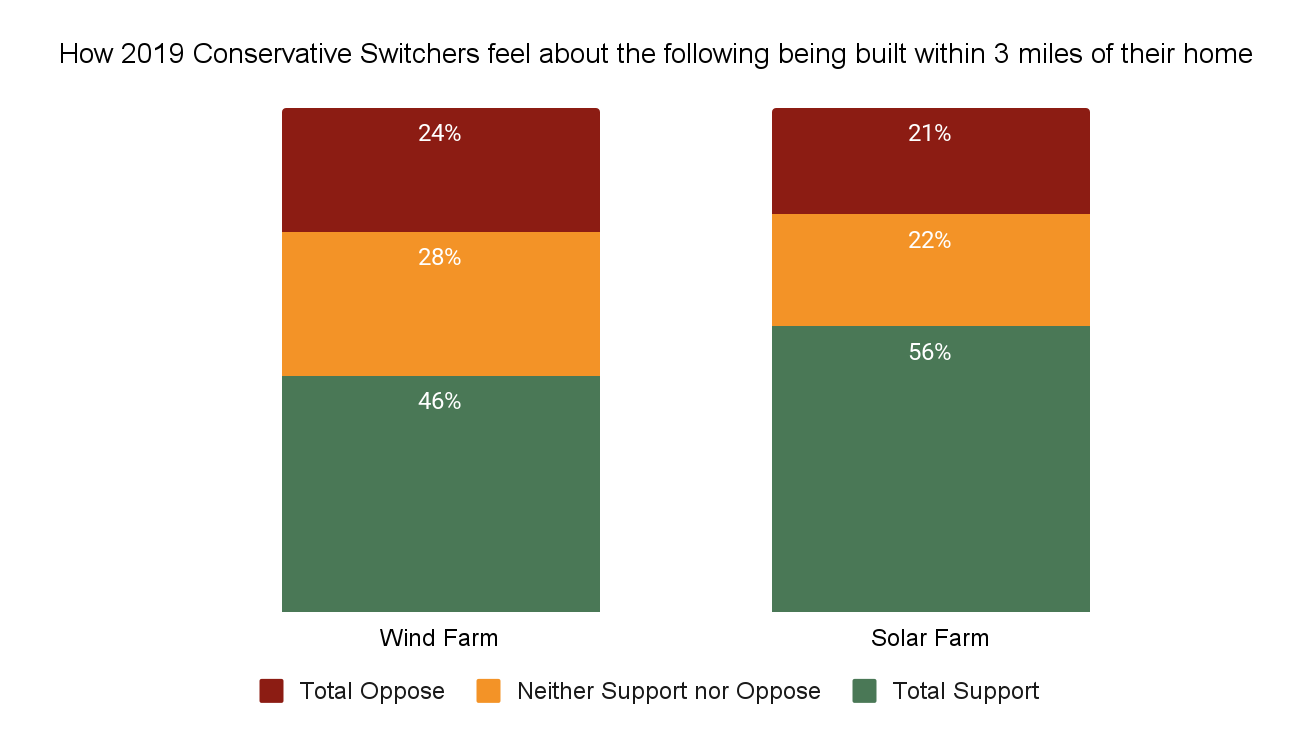

There is still a reflex, learned under a Tory government, that planning reform is dangerous and unpopular. Not of course that this was ever proven. In the case of support for local renewable energy - quite the opposite. It was always that it was unpopular with the people that Tory MPs spent their time with. Opponents of development tend to skew older, wealthier and more conservative.

Focusing on the small and noisy misses two things:

Most of the public has no fixed view. Public First research suggests they get the upsides, but have pretty legitimate concerns about specific downsides locally. They are opposed to practicalities, not in principle.

This is even more true for those who vote for the Labour Party, with only a tiny fraction of its vote share opposed to development on principle.

Labour isn’t worried about the people that the media tell them they should be worried about. They are worried about, shock, the vast majority of the public. Labour, unlike the previous government, also has a network of pro-build MPs, not just passive Wets who would quite like some houses but not enough to say so out loud.

That allows Labour to go hard on clean energy. Even for pylons, our research finds (slim) net support, but crucially once built, people just accept them. The asset risk is in the development stage - is there lots of noise and disruption from construction or does the public feel they are in the right place? Community and individual benefits help move more people into firm supporters but none of this is about planning policy.

Housing is a different beast. The challenges here are steeper and acceptance isn’t as high. PF has found concerns are emblematic of deeper issues the public has with the country: housing doesn’t have adequate infrastructure or public services; it’s unaffordable; or doesn’t suit local needs.

The planning system is supposed to deliver these things. Lots of developments do include the right houses or new services but misunderstanding is rife. Where they don’t the challenge comes from labour and supply chains. For developers to build at speed it is much easier for them to pay a surcharge to Local Authorities instead of waiting for other infrastructure. In theory, local authorities should use this money to build services at their own pace, but it's far too easy to see it as an income stream to replace central government cuts.

One option both for concerns over location and strain on services would be more but smaller developments. Yet our low-resource planning system doesn’t incentivise that. Another would be to remove get-outs for developers, but that could slow delivery. Central government could pay for more things directly where they want houses built, but that’s not cheap and not exactly in keeping with the idea of public-private partnership that Labour has pushed.

Even with reforms, a low-capacity system that incentivises only one kind of housebuilding (big uniform sites), and therefore plays into public concerns and potential opposition, can only get us so far.

Labour needs a plan for what happens when the existing planning system, doesn’t deliver. This is more of a political economy challenge than a public opinion one.

Broadly there are two groups when it comes to planning reform. Those who absolutely think you should ditch the current system because it will mean less consultation and more speed, arch-YIMBYs. And there are those (like government) who think playing within the rules of the current system can really be made to work if the right people do it.

The issue with the former is those are the arguments most likely to stoke opposition. They argue for revolution, something the British public never fancies The issue with the latter is that no room for failure. Add in, for example, the large environmental NGOs burned by post-Brexit rule changes and wary of risks to the environment from a new system, and we get stasis.

Starmer’s refrain in politics has been about the importance of playing by the rules. Whilst government is trying to make the current rules work, this is also Labour’s escape valve.

Currently planning decisions are arbitrary, there is a postcode lottery about what gets approved based on your local authority and the noisiness of your neighbours. We don’t get decisions or processes that mean the majority of voices are supported. New Zealand successfully expanded permitted development to build more, quickly. In a certain place, a certain type of housing, go ahead and build. Not full-scale zoning but on the way. Something implemented by a Labour government, with support from eNGOs and others, that saw both economic and electoral benefits from it.

Government should set up any potential failure to meet infrastructure goals as a test of the planning system, not themselves. Is it a fair system, delivering what communities need? A different system is positioned then not as a new thing, but as the way to achieve what Labour has been saying all along.

The work that needs to happen now then is to change the political economy on planning - encouraging Westminster and thoughtful institutions within it to explore the policy detail and messaging. Whilst, getting the media to focus on the actual concerns of the majority - access, affordability and appropriateness, rather than to go straight to the most vocal opponents. Labour will need an escape valve to hand for if playing by the rules means it runs out of time on its target.

Thanks to the always excellent Yasmeen Sebbana and Bertie Wnek for both their research and their input