EE#35 Not everyone in the countryside is a farmer

Turns out rural voters think like everyone else

Farmers threatening to stop accepting sewage have reminded Westminster that the countryside isn’t just somewhere to visit on weekends. Unfortunately, the response to Rachel Reeves’ changes to agricultural inheritance tax, has once again looked at the UK’s towns and villages solely through farming. Rarely, if ever, does SW1 stop to think about those people not threatening to launch militant action, or what they might want.

It's understandable why rural voters get little attention. Just under a quarter of UK constituencies are rural - 158 in total. This is roughly the same across each nation, bar Northern Ireland. Compare that to the US where between 42 and 64% of congressional districts are sparsely populated or rural.

Shockingly, despite their minority status, rural voters think like the rest of us. According to research earlier this year based on British Election Study data “on most dimensions of public opinion, we generally find little difference between rural and urban”. Where they do differ it’s marginal. They are slightly weather and slightly more right-wing than the UK as a whole, though less so in Scotland.

In an era of anti-trust, there are no significant differences in trust in government or populist sympathies (though rural Scotland weirdly seems to have a bit of a thing for authoritarian leaders). That stands in contrast to our neighbours. In Europe, rurality is closely tied to support for populists, and characterised by greater distrust than their city-based compatriots - likely why recent EU farming protests allied with the far-right.

It’s the same story on issues. Public First polling shows rural voters care about the cost of living, the quality of the NHS, the state of the economy, and immigration. The same as any other group. Relative levels of support for those things vary slightly. Immigration, for example, is more intense, as are concerns about the NHS and other public services.

There are two obvious reasons for this beyond political sentiment. Rural communities are smaller, and even low immigration is more immediately noticeable. Rural access to services is already hard, they’re sparser and transport is worse than in urban areas. Closures mean going from not much to nothing. Far then, from protesting against inheritance tax changes, rural communities are crying out for the funds it will raise to go to their services.

One of the responses to EU farmers kicking off was to downplay or walk back climate and environment policy. That would not play well here. Climate, through flooding or drought, can be much more salient to rural voters. In a massive poll for Onward last year, rural voters (especially Labour-leaning rural voters) were dead keen on wind and solar energy on their doorstep. Like voters in general, rural communities see renewables as providing cheap energy and energy security. Again Labour’s plans are in line with what rural communities want. This is one area they overlap with farmers who are massively pro-solar for example.

The UK's rural seats, driven mostly by England and Wales are more likely to vote to the right. Labour has undoubtedly grown its rural presence, winning 45 new rural seats compared to the last parliament. Given it only had 4 going into July, that's a serious increase.

The Conservatives represent 35% (57) of these seats and Labour 31% (49). Despite Starmer having more than three times the seats overall than the Tories, he still presides over fewer rural seats. The Lib Dems also outperform with 31 rural seats (20% of the total), whilst only holding 11% of seats overall.

But what does that mean for political strategy? What matters is a) what proportion of your seats are of a given characteristic, and therefore the internal pressure on party leaders; and b) who you're fighting in those seats.

Labour's seats are predominantly urban. While almost half of the Tories' remaining seats are rural, just 1 in 8 of Labour's are. It’s a feature, not a bug that the Minister in charge of rural affairs, Steve Reed, sits in an entirely urban seat.

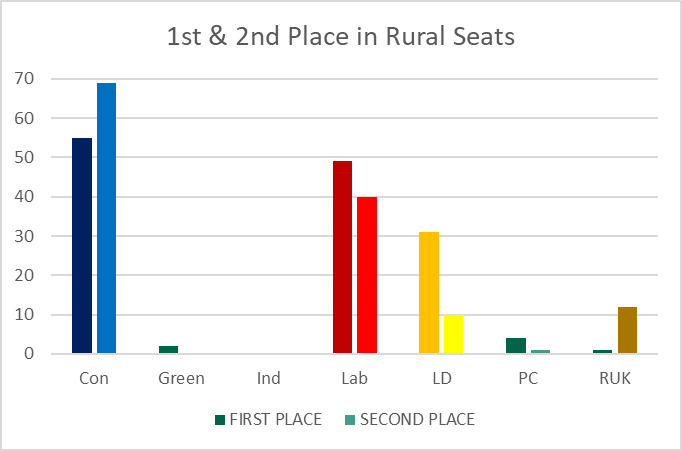

Political competition though is interesting. Rural seats are more marginal than others, with the average majority at 5400 compared to 8400 in cities. Unlike Labour’s more urban seats where it is facing in at least four directions, the rural picture is much more of a straight Labour-Tory fight. The Tories are second in almost half (69) of the 158 rural seats, with Labour behind in 40.

Labour should be comfortable with its inheritance tax plans. While rural voters generally are more right-wing, they are far more concerned about the state of public services. While there are 174,000 farmers in the UK, there are almost 12 million potentially winnable rural voters. The next run of UK elections will be in Counties next May, and Scotland in Wales in May 2026. Labour’s mayors also govern significant rural areas across the country. Rural seats may not be the majority, but they could well set the narrative for Labour’s parliament. Labour can’t let farmers set that narrative. The dividing line on tax and public services is one it can own against the Tories but it has to be clear this is part of a cohesive offer to rural communities, not just a series of isolated Treasury decisions made without thinking about them.