EE#5 Ain’t no party like the Green Party (Eng & Wales)

The real Green threat is not party political

Sandwiched between Conservative conference in Manchester and Labour in Liverpool, this weekend Brighton will host two days of Green Party activists. The Green Party of England and Wales is a strange beast. Brighton in theory is their spiritual home and the location of the party’s only elected MP. But the sands of the Sussex shore are shifting. The party lost its minority control of Brighton and Hove Council in May, keeping just seven councillors. With the long-serving Lucas standing down at the next election, the Westminster seat could follow.

Yet despite losing their flagship council, May was also the Green’s best-ever local election. Following recent success in cities, the party is gaining ground in more unexpected places. In an election already being shaped by climate, this week we look at what role the UK’s only environmental party might play.

Although around in some form since 1972 the Greens didn’t assume their final form, their Venasaur if you will, until 1989 when they split into three independent national parties. The subsequent rise of New Labour was not a good period for this new form. Although growing steadily, the party’s vote share didn’t cross 0.6 per cent until 2005 when they hit the heady heights of one per cent. Even in 2010 with the breakthrough in Brighton, the party nationally fell back.

Instead, it was 2015 that proved to be the green high-water mark nationally. This was the first election where the Green Party of recent memory took shape, holding Brighton comfortably but also proving to be a contender in Labour cities, coming second in Bristol West and Sheffield Central as well as seats in Manchester and Liverpool. Success was thin however, besides these four second places, the party only finished third in a further 19. The Greens were hit hard by Corbyn’s Labour in 2017, before a slight recovery in 2019.

Greens do best in the South East (3.9 per cent) and South West (3.8 per cent) which is almost twice as well as Yorkshire (2.3 per cent) or the North East (2.4 per cent). Given their success initially in urban areas you might expect better results in the London Assembly, yet their vote share averages less than ten per cent. The next London mayoral election will be the first fought under the first-past-the-post system; you can imagine this change squeezing the Green vote further in 2024.

Unlike the Lib Dems, the Greens don’t overperform in by-elections. Somerset and Frome this year provided them with their best-ever result, a third-place finish at 10.2 per cent. The party has only crossed five per cent three other times, Selby and Ainsty that same day, Norwich North in 2009 and Haltemprice and Howden in 2008.

Recent local elections though offer a better insight of what role the Greens could play in the next general. The locals in 2023 were the Green’s best-ever, gaining almost 250 seats - well above any previous attempt.

The Greens took their first majority council in Mid Suffolk, and became the largest party on seven other councils, East Hertfordshire District Council, Lewes District Council, Warwick, Babergh, East Suffolk, Forest of Dean and Folkestone & Hyth. With the exception of Warwick, every seat (using 2019 boundaries) covered by their 2023 local success is Conservative-held. These do not look like the winning areas of the 2010s when the Greens were challenging Labour in cities. In the 2019 General election five of the Green’s top eight performing seats were in Tory heartlands.

The Green Party is now a coalition of two types of voter. The climate left, which dominates the party in urban centres - a stereotype of these voters would have them placing social issues alongside emissions reductions, wanting to use the transition to reshape the economy away from capitalism - unfairly called watermelons for their green outside and red insides.

Then there are the older, more conservative rural voters behind the party’s more recent success. These voters represent a more English view of ‘green’, concerned with protecting nature rather than reducing emissions. Key to these voters is opposing development, in favour of a green and pleasant land. As James Heale recently pointed out “half of voters who want to prevent excessive building see the greens as their allies”.

Many of the candidates that won locally in 2023 did so on anti-housing or anti-development messages. Nationally, the Party is anti-HS2 and opposes many housebuilding policies including development targets. Obviously, the Green Party is not anti-renewable energy, but I can’t see much evidence of them actually wanting it built anywhere, and certainly, there’s no view that planning is an impediment say to onshore wind. Suffolk, the site of their biggest recent victory is particularly acute. East Anglia is where much of the UK’s offshore wind needs to land. That means pylons to transport it from a sparsely populated coast to English towns and cities. The Greens don’t want pylons, instead advocating an undersea grid. Given the cost of underground cables, let alone undersea, is ten-fold more than pylons on average, and that it's quite hard to get to say Birmingham by sea, this amounts to a no clean energy policy.

This is one of the ways the English Greens diverge from their overseas equivalent. While the German Greens have a strong climate left contingent (the Fundi), the party is dominated by a faction known as the Realos. The leadership is environmentally minded but aware of the trade-offs of power having led or co-led many regional governments. Germany, like the UK, has dilapidated infrastructure and has struggled to cut emissions. In 2021 the party went hard on building to alleviate these woes. Unlike English Greens, the Germans are also hawkish on defence and security, and strongly pro-Nato.

The English Greens also have a challenge that a party like the Australian Teal Independents don’t. This small group of pro-climate, female campaigners took several seats from incumbent Australian conservatives. While this was also partly to do with the Liberal party’s deteriorating standards in office it was made easier by the Teals’ ability to hold the same message across seats. English Greens are going to go into an election challenging traditional conservatives, but with manifesto commitments including legalising all drugs or universal basic income. That’s no comment on the merit of any of those ideas, just that it's quite the straddle.

The real green threat

Although a recent poll put the Greens at eight per cent nationally, it’s hard to see 2024 as a breakthrough year for them.

In terms of a direct threat to Labour, the two seats where they did best in 2019 would require around a 20-point swing to deliver Green MPs. More risky for Labour is the indirect impact. I didn’t just include Stroud above for parochial reasons, it's emblematic of where the Greens cost Labour a seat in 2019. The Green Party share was more than the majority in several 2019 Red Wall seats including Blyth Valley, Heywood & Middleton and Bury South. Though admittedly the absolute number of green votes is small.

Similarly, although three-quarters of the Greens local gains came at Tory expense, the direct threat to the Conservatives is low. Suffolk (2019 boundaries) still requires a 26-point swing, though that’s obviously only if the Labour vote remains static.Though if the Greens do hit eight per cent and most of those gains are from Tories, there are more seats that Labour can come through the middle.

The Green Party could also play a similar role to UKIP or voting in the Brexit referendum. Not all voters flooded straight from Labour to Tory in the 2019 general election. Many needed an interim less jarring step - whether this was not voting for a while or voting for a third party. For long-time tribal Tory voters, the Greens could offer a step away, on the way to Labour.

The final effect on the Tories comes from the uncertain impact of progressive alliances. Alliances are challenging. You have to identify who is best placed to win based on different baselines, in none of the seats where the Greens did well in locals were they the second largest party in 2019. Then other parties have to choose to pull out, which in Stroud for example the Greens did not do. That’s before you get into the assumption that anyone voting for each of the other vaguely left parties is happy to vote for whoever remains. As by-election results show, the Greens often get squeezed. Recent local green gains have come on the back of increased turnout. If those people turnout again in 2024, but the Green Party doesn’t look viable, it could mean new votes for Labour.

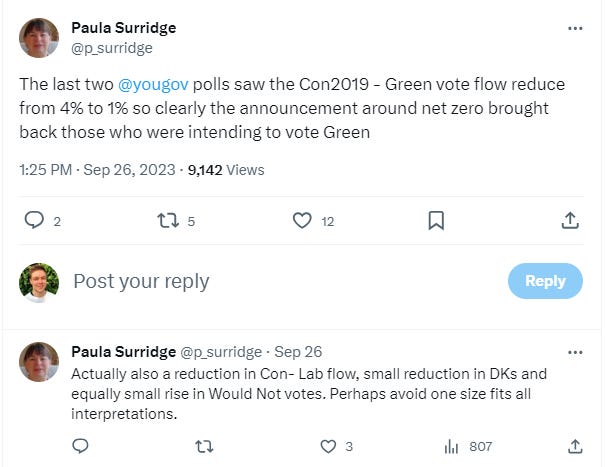

Personally, I think this week’s HS2 announcement is more consequential

It’s not the electoral risks that keep me up at night. It’s the direct impact on our ability to build clean energy. The Lib Dems have shown that opposing development is a viable electoral strategy, and one that can force changes to Conservative policy nationally like after the Chesham & Amersham by-election. The Greens are following that model on housing, and increasingly on pylons in East Anglia. Green pressure on infrastructure in Tory heartlands is going to exacerbate a general Conservative cooling on renewable energy. If Labour sees a route to victory in these seats it’s candidates could easily get sucked into the same opposition,

The UK’s only environmental party has a responsibility to not follow in Government’s footsteps. Reaching net zero nationally means building stuff locally. The two things are mutually exclusive. While Green Conference might not get much media beyond fundraising for a major legal battle, the party’s policy platform and where it puts its resources could play an outsized role in the next election, it's definitely worth Labour and Conservatives sending a couple of people in preparation.

Takeaways

The Green Party has never broken through in national elections, but recent success in local elections could influence the next general.

Greens now pose as much if not more threat to Conservatives in their heartlands, especially the South East, than to Labour

But to win those seats Greens are taking anti-development positions. While it may work it could damage our ability to hit net zero, especially the role out of clean power.