EE#2 How to Spend It: Labour's £28 billion

Labour's boldest policy needs bolstering against economic and political forces

Labour’s new top team has some work on its hand. Two years after launch their biggest boldest policy, £28bn of green investment is reportedly being scaled back. Despite the coverage, what Reeves actually said is that fiscal rules come first, and climate investment will need to fit within them, something confirmed by this week’s National Policy Forum.

Labour is trying to both campaign for change and present itself as a trustable government. Now, fiscal rules and green investment are not mutually exclusive, but Labour needs to balance the sobriety of the former with the excitement of the latter . The £28bn, or Green Prosperity Pledge, is and should be Labour’s main retail policy for 2024. But for it to get there there are both economic and political challenges to overcome.

More than a number

Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves originally announced a £224 billion, eight-year green investment plan in September 2021. For a hopeful resident of 11 Downing Street, it was radical (more than Corbyn had promised in 2019), and as expected from a former Bank of England economist, rational.

“I am committing the next Labour government to an additional £28bn of capital investment in our country’s green transition for each and every year of this decade” - Rachel Reeves, Labour Conference, September 2021

The UK has an investment problem. A lack of both public and private spending is holding back growth (see George Dibb’s excellent explainer), and decarbonisation. While private investment in the transition is growing, it is not growing fast enough and remains concentrated in developed markets where the route to emissions reductions is more obvious, like renewable energy. There is little in say greening housing or agriculture.

Net zero is a challenge created by public policy (though responding to external circumstances). It is also complicated, and investors don’t know enough about how the UK should decarbonise. Businesses all say the same thing, they need help. Government should set a path and lower risk so that they can invest with confidence. Labour wants to use public investment to do that, crowding in private capital and hopefully kickstarting growth.

State funding can also provide leverage. Targeted funding, conditions on cash, or good old-fashioned industrial bargaining should allow government to push the outcomes it wants to see - notably emissions reductions. That diagnosis is shared by other progressives like Joe Biden in the US, where record investment through the IRA and CHIPs act is having a substantial effect on private investment, and bringing with it social goals from union membership to childcare provision.

The GPP then is the return of industrial strategy. What has been lost over summer briefings is that from the outset the £28bn was always a jobs policy, intended to build supply chains in Britain. Labour saw green technologies as the most viable route to do that, it just so happens that will also reduce emissions. Tackling climate change is the bonus that comes with economic change.

What does £28bn get you?

According to the Climate Change Committee, decarbonising the UK will cost around one per cent of GDP per year to 2050. Several organisations have looked at what those specific investments required to meet our carbon budgets are, notably IPPR’s Environmental Justice Commission and Green Alliance’s Policy Tracker. These, amongst others, were instrumental in helping Labour understand the scale of the challenge and the economic benefits of action.

Despite buying the rationale behind the total, Labour didn’t sign up to an itemised list of commitments. Reeves and co were also more targeted, for example, money was only for physical capital, in keeping with Treasury definitions (whatever George Osborne would stand outside in a hard hat), excluding for example skills funding.

Since 2021 the party alongside business and civil society has been working hard to identify specific investments. Labour’s goals as an opposition party differ from a government or lobbyists. It is not for opposition parties to set out every penny, the civil service will write the net zero strategy if Labour gets there. Opposition spending pledges must a) demonstrate the party is responsible enough to govern, and b) that that party will do things in the voter’s interests when it gets there. So yes it needs to meet the economic and climate objectives Reeves spelled out, but it also needs to meet political goals that will get Labour elected and ultimately able to spend.

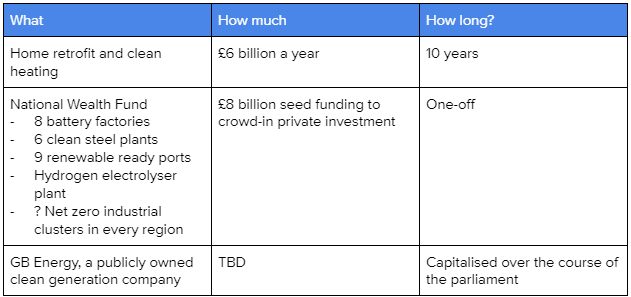

That means that Labour has allocated some big numbers to a mixture of issues the public is attuned to (poorly insulated homes) and areas that show how Labour values are different from Conservative (green manufacturing). But as the table shows, having only £68 billion (of an initial £224 billion) publicly allocated makes the rest of the money vulnerable to ‘scaling back’. Once an interest group thinks it's getting something it's hard to take it away - if there are no political losers, it’s much easier.

Why are there wobbles?

It’s the economy stupid

The list of things to blame Liz Truss for is long, but it has to include the fortunes of the £28bn. The market reaction to her unfunded borrowing for untargeted tax cuts cast a long shadow over government spending. There is though a stark contrast between time-limited borrowing to update the UK’s decrepit infrastructure and a perpetual tax cut with no proven link to economic growth. It’s incredibly unlikely after Reeves’ first budget that there’ll be market turmoil for spending on things business is asking for.

Inflation has made worries worse. Interest rates are 5.15 percentage points higher than September ‘21. Borrowing now costs more, and that makes it harder to square with Labour’s plan to have debt-to-GDP falling. But inflation also reduces the effective size of Labour’s pledge. £28bn in 2021 would need to be £33bn in today’s money, and that’s just using the average inflation rate. Construction of wind turbines for example is up 40 per cent. This is compounded by a falling pound which has lost almost 20 per cent of its value since the GPP’s launch. At least initially net zero requires things to be made overseas, a weak pound makes those imports more expensive.

Finally, there is Increased international competition. The GPP was the Inflation Reduction Act before those three letters were a twinkle in Joe Manchin’s eye. But now big players are on the pitch. The IRA, and the EU’s response, restrict choices a future Labour government can make as others secure private sector commitments first, and increased demand reduces pulling power.

Only politicians say it’s the economy stupid

Economic challenges can be dealt with. For many, they are just an excuse for run-of-the-mill political objections.

As crumbling concrete in schools is showing, the transition is not the only area lacking investment. While choosing where to spend is an economic strategy problem it poses a political challenge inside Labour.

Shadow ministers rightly want capital spending in their own brief, but Pat McFadden, and presumably Darren Jones too, is tough to convince. This can make trimming the £28bn to direct money to their preferred projects seem more appealing.

That desire in part comes from the view the £28bn isn’t doing enough to win new votes. Part of that is not knowing quite how popular climate is with voters (see EE#1). But briefings have also said they want a greater focus on jobs than climate, pointing to Biden’s ‘securonomics’ - forgetting that the majority of those jobs are from the US’s green investment.

The final challenge is real, and deeply ingrained in the Labour psyche - being trusted to handle the economy. Current polling the public believes they can, very much so, yet cooling the pledge is an effort to that lead. But as Luke Murphy and I wrote in December using data from the excellent Steve Akehurst:

“Polling by Opinium prior to the [2022] mini budget shows that a generic call for a multi-billion climate investment package receives 68 per cent support, with just 21 per cent opposing. This falls marginally to 59 per cent support when paired with a statement that investment will come from borrowing (+34 net positive).

For Labour, support reduces to 61 per cent, but remains +35 net positive. Support falls to 52 per cent (+22 net) when paired with borrowing. This is driven by reduced levels of support in non-traditional Labour voters. For the Conservatives, there is much a smaller brand penalty.”

There is a real brand penalty for Labour spending that the Tories don’t get - but the voters you lose are not the swing voters Labour needs to win, and the policy remains overwhelmingly popular.

What to do instead?

The economic challenges

Green investment will remain in a holding pattern until Labour squares it with their fiscal rules. Carsten Jung shows that an additional £30bn annual investment is compatible with falling debt to GDP over five years but requires growth impacts to be lasting not temporary. Others, like Andrew Sissons, have suggested adapting rules to make room for climate investment. We’ll do a future piece on green fiscal rules but I worry having a large sum outside of Labour’s rules will be poorly understood by the press and willfully misunderstood by the Tories. The options I think sit with the pledge itself.

Ditch the pledge. The public hasn’t heard of it, fiscal conservatism like in 1997 is the route to victory. You can always do something else when you’re in government. But this throws away Labour’s central dividing line with the Tories, its theory of change on the economy, and its most developed policy. It’ll aggravate the base and prove Tory attacks on the pledge right.

Reduce the total. Labour could say the government has made progress meaning they don’t need to spend as much, or that the Tory economic malpractice has caused them to rewrite plans. But as we’ve seen the sum is already smaller by virtue of inflation. This has the downsides of the first option but reduces the upsides of long-term investment.

Borrow less. £224bn of spending needn’t be £224bn of borrowing. You could repurpose wasteful spending, the National Audit Office in 2021 pointed to £17bn a year in environmentally damaging tax reliefs. The £26bn capital on road expansion is also difficult to square with net zero. More politically challenging would be new taxes that raise revenue. Labour could use investment to take equity stakes that payout and reduce borrowing requirements in later years.

Change the pattern of spending as Luke and I said last year, getting £28bn out the door in year one is incredibly difficult, the supply chains aren’t there and spending programmes aren’t set up. A phased approach would make more sense, starting modestly before ramping up rapidly as markets grow - borrowing less now and more later. This should also include setting out what form borrowing will take. Green bonds this year raised more than traditional ones, while the last set of government green bonds was 12 times oversubscribed.

The political challenges

Clarifying the level of borrowing will alleviate some of the political challenges, but there’s more to be done.

First, as Keir Starmer likes to say Labour’s plans are as much about the how as the what, but that’s currently missing from the £28bn. In our paper last year we set out how a statement of principles for what any public investment is trying to do is important for market and public confidence, demonstrating that its responsible and effective.

Second, Labour will need to define what it means by green. There is a difference between spending money to directly reduce emissions and spending money on projects that are compatible with net zero. Aligning with the green taxonomy guidance will help but I think Labour may end up saying money is available for additional green schools or climate-friendly hospitals, even if this isn’t idealy from either a jobs or climate perspective.

In return shadow ministers need to focus on how to use green capital for their goals, think green space expansion as a preventive healthcare measure. I’d push to widen the scope of capital to include human capital making it more relevant to other briefs. It’s all very well having shiny factories, but they’re useless if there aren’t skilled workers to fill them. A wider scope also makes other retail policies like loans or grants for EVs easier. Steve Akehurst argues that the best way to inspire support for climate policies is by talking about future generations, climate impacts and global leadership - which all beat the co-benefits of action (like economic growth). But when we are talking about public spending messaging needs to be tangible to voters.

Finally, and the hardest, the £28bn needs to be broken down by space. By-election candidates or regional leaders need to be able to say how much is coming to their area under a Labour government and point to what that will deliver. There’s some indication of this with jobs numbers, but even eight battery factories can’t be everywhere.

Those in Labour rightly say they will only get to spend any money if they win, and that policy changes and rhetoric of fiscal responsibility will do that. But retreating from one of if not the most popular policies Labour has would be a mistake. The £28bn remains the right policy for the UK’s ills; the new shadow cabinet’s job will be to secure buy-in across the party to champion that.

Takeaways

Significant public investment is required to address the UK’s economic woes and de-risk green markets.

Labour’s attempt to do that with £28bn green investment has been challenged by increased costs of borrowing and internal and external critics.

Setting out how the money will be raised, how it will be spent (not on what) and using some of the money for more traditional retail politics could sure up its support.