If you’d been locked away for the summer, or on sabbatical because you know 2022 was all a bit much, would September’s climate policy look any different to when you left? Squint and it could even be a decade ago. Rain ruins a crucial Ashes test match in Manchester. Europe is literally on fire. The Prime Minister is promising to cut green crap, despite the green promises that brought his party to power.

Yet unlike David Cameron in 2013, Rishi Sunak hasn’t actually ditched net zero and major planks of the policy still stand. A new Patridge-esque battle for motorists is rhetorical, we still have the 2030 ban on combustion engines - as I’m sure government knows - an electric motor is still a motor. There’s an opportunist review of low-traffic neighbourhoods, which while beneficial for climate, are for air quality, not net zero. And finally, 100s of new oil and gas licences, despite the fact these are handled by an independent regulator and come in a future where it’s unlikely Sunak will be PM. Labour, despite some wobbles post-Uxbridge, and a darkening economic cloud is still committed to its package of green industrial policies.

Why then are both parties backing away from climate comms if their policies are unchanged? While it doesn’t feel like we’ve gone far since 2013, things have moved on. David Cameron’s 2013 decision while extremely costly for households would be ruinous now, both politically and economically. Net zero like it or not is going to be central to the next election.

What am I reading?

This is the first post from Election Energy a fortnightly (at least) newsletter on policy and political issues in energy and climate as the UK heads to the next General Election. It’s free to all, with additional exclusive paid content. It will aim to do two things. One - get under the skin of public opinion. Polling the popularity of onshore wind for example is money for old rope - but we know little about support for the pylons that bring the electricity from those turbines to homes.

And two, point to trade-offs in policy, not utopias - the UK is small and we can’t do everything. We’ll try to look abroad to see who’s doing things faster, better or smarter than the UK - and not just the US or Germany where Westminster normally looks.

If that sounds interesting subscribe to get it directly, and please share with others who might like it too.

Climate’s role in 2024

Climate change can feel overwhelming - half the world is currently under exceptional heat, fire or flood (which El Nino threatens to make worse) - yet for government climate and energy remains just one problem amongst many, and in recent history a second-tier problem at that. Still, I think three things suggest that perhaps for the first time, it will be far more electorally important than before.

People really care

Other countries have got there first

Climate is now ideologically competitive.

1. People really care

Rewind to 2008, UK concern over climate change was growing. New Labour’s Climate Change Act received only three votes against, and then opposition leader David Cameron was putting green at the heart of a Tory rebrand. However, come the financial crisis, support turned out to be fragile, and economic concerns wiped out climate’s emerging priority concern. Polls saw growth in climate scepticism and views that scientists were exaggerating the threat.

In the 2020s the story couldn’t be more different. Despite dire economic outcomes for households post-Covid, 75 per cent of the public remain concerned about climate change with 84 per cent worried about its impacts. Support for net zero as a policy polls similarly. Whether it’s the government, Office for National Statistics, or British Election Study climate change is a top four issue nearly all of the time, and often a top three issue.

Concern is important, but salience is what drives votes. Climate has been a consistently top four issue according to the BES over the past few years, but there is still a drop off from issues like the economy or the NHS. With El Nino arriving the weather, notably extreme heat (and ruined summer holidays), over the next few years is going to be a consistent media story. That coverage will increase salience.

And as the cost of living worsens, the public is increasingly connecting that to climate. About half the population think that addressing climate change is good for the economy, while 70-80 per cent depending on the poll see renewable energy as the way to tackle high energy bills.

While some in Westminster still imagine this is the preserve of young, wealthy or urban types (a Venn diagram with no middle) that couldn’t be further from the truth. In an analysis of British Election Study Data my former colleague Brett Meyer at the Tony Blair Institute shows that everyone is more worried about climate, and while the oldest are still the least supportive, that gap is closing.

“Concern is not just high but increasing across age groups, income levels, and urban and rural areas, while the gaps between different demographics are closing. (Meyer & Lord 2021)”

General population is fine, but politicians care about where. Labour is obviously concentrating on a particular set of voters and seats. But as Tom Sasse and I wrote in Autumn, pick a ‘wall’ and you get the same result.

“Seven in ten red wall voters support the net zero target, while 94 per cent say that action to cut emissions is important to them. In a poll of 41 blue wall seats, seven in ten want more ambitious action, while over half said that the government wasn’t doing enough.”

Preferred solutions to this monumental challenge are poorly understood and not helped by single-issue polling. We do know that renewable energy polls consistently well, and out-polls its fossil fuel alternatives, as do individual solutions whether that’s more public transport or switching to heat pumps. Support dips due to a range of factors like when cost is mentioned (either for government or to the individual), inconvenience and most commonly a lack of understanding. But contrary to the coverage over the summer in this way net zero is no different to any other policy, even support for the NHS falls when rising costs are mentioned.

Similarly, the public is supportive of individual behaviour changes, mostly where those changes are about reducing damaging behaviours rather than abstinence. However, unfortunately for Conservatives, households overwhelmingly see it as government’s role to lead behaviour change and help them to as well.

2. Other countries got there first

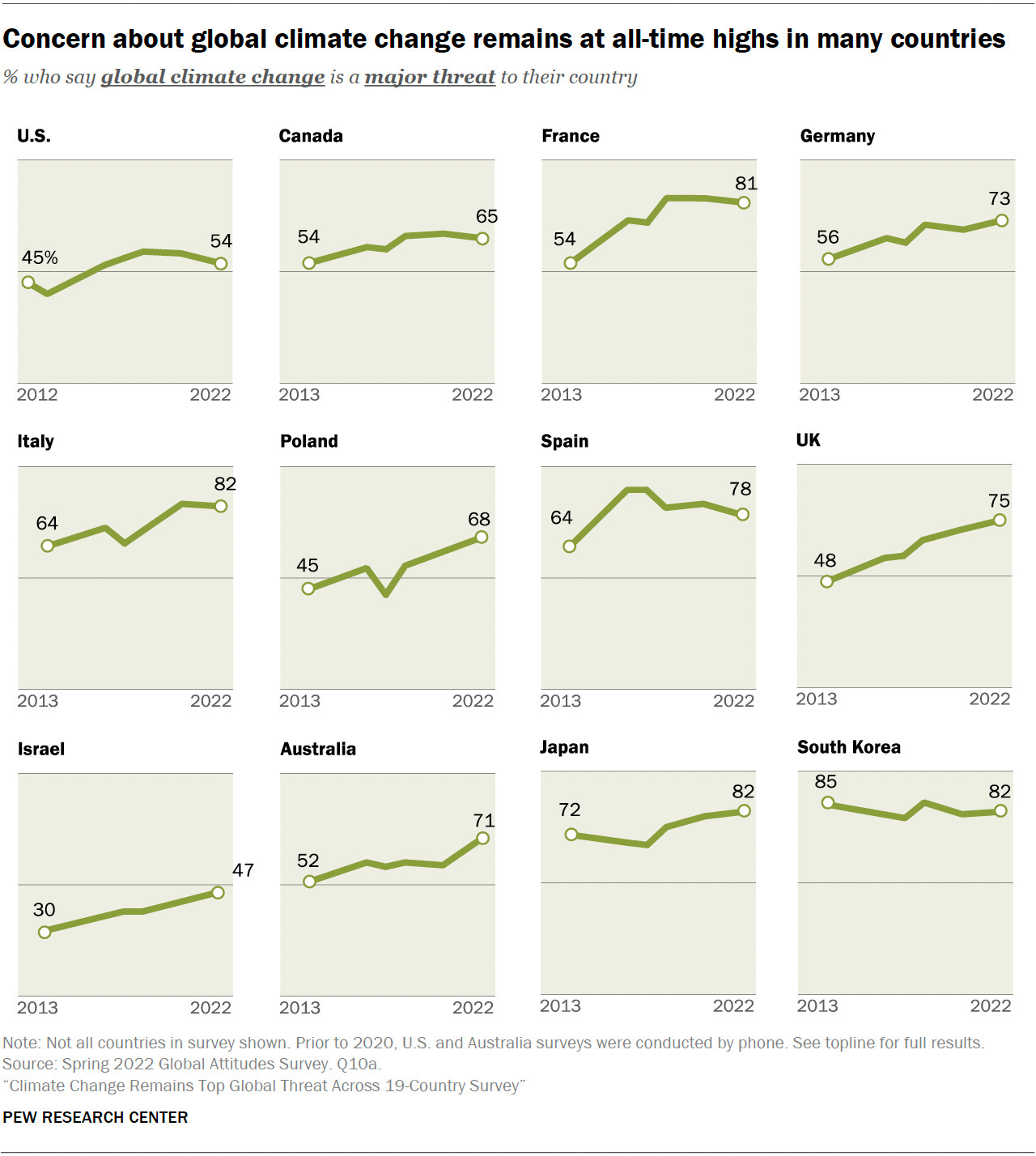

If you take Pew’s global threat index as an indicator of climate concern, the UK ranks alongside similar countries. We see climate change as a slightly bigger threat than the average German or Australian, a lot more than the US, but slightly less than the supposedly climate-phobic hi-vis-clad French. What stands out though is that each of those countries has had an election recently shaped by climate politics.

The Australian election in 2022 was dominated by climate. The rightwing Liberal Party had long railed against climate policies, with Prime Minister Scott Morrison famously bringing a lump of coal to Parliament to prove how ‘scared’ his Labor opponents were of the stuff. Yet Liberal inaction on climate change emerged as symbolic of their disconnection with public opinion and became embroiled in concerns about impropriety in public office.

Climate fractured the traditional two-party system in both directions. The new Teal Independents, a centre-right group of female independent candidates campaigning for standards in office and climate action blew away conservative big beasts, including the seats of former chancellors and prime ministers. The Labor Party wasn’t spared, despite ultimately winning, they lost several urban seats to the Greens, including that of their shadow environment minister.

Germany told a version of that story too. Following catastrophic flooding, rising concern over the effects of climate change drew voters away from the Christian Democrats to the resurgent Greens. The SPD emerged as the largest party largely by keeping their heads down.

Canada saw similar effects in their federal election following the heat dome in 2021.

In the US, Biden (eventually) made climate central to his offer after being pushed from his left in a slightly too close Democratic primary. However, this messaging and policy was not jettisoned in the general and Biden now has all the zeal of a convert, doubling down on green industrial policy as a new deal for the working class and using it as a point of difference with Republicans. Both Lula in Brazil and Macron in France used similar rhetoric in the face of a challenge from right-wing populists.

The UK is none of these countries. These elections have taken place either in Presidential systems or with proportional voting. The UK has tried a centrist insurgent party recently and I won’t hold my breath for ChangeUK to take Jeremy Hunt’s seat. Our Green Party is less mature and more localised than the German Greens. There are also comparable elections where climate hasn’t featured, or the result was a backward step - notably in the Nordics with Sweden and Norway.

However, British parties and politics are paying attention to these harbingers. Keir Starmer is modelling his public image on the RuPaul-esque vibrance and charisma of Anthony Albanese and Olaf Scholz - two beneficiaries of climate fallout. While those informing Labour Party policy are borrowing heavily from Bidenomics. Australia’s outcome has led both the Conservative Environment Network and Tory think-tank Onward (using Public First research) to warn of the piles of lost votes if the party decides to ditch green.

3. Climate policy is ideologically competitive

That climate has been a wedge issue elsewhere makes it much more interesting for politicos. We are well beyond hidden changes to power generation, decarbonisation in 2024 means tangible change. Policy will dictate how the burden of that change is spread across industry, individuals and government. Decarbonisation is now inseparable from economic policy. The tools to tackle it cover investment, regulation, and ultimately market intervention.

We can already see the ideological divide between Tories and Labour on climate and energy as emblematic of their wider approach to governing.

Labour sees decarbonisation as the archetypal challenge for the state. In their minds, and borrowing heavily from the Biden playbook, it requires interventionist governance and a strong industrial policy. That means a new form of public-private partnership, where public cash comes with heavy strings attached in an attempt to hang wider social goals (say job creation or childcare provision) off of growth in new green industries. Labour though remains cautious about talking about how people live their lives. As Robert Shrimsley has written, Starmer and those around him have recognised a natural small c conservatism in the British public that needs to be respected. Like the Tories, to Labour, the bulk of decarbonisation will be led by the business sector. The difference is that business will receive government support to make that burden feel lighter.

The Conservatives are more muddled. The rhetoric is that market solutions and the private sector should be able to get us there. In practice, this has meant little active policy beyond a commitment to the CfD scheme (at questionable prices), and long-term targets. While this has worked for EVs, various attempts at market mechanisms for heat pumps have failed to move the dial.

Without much desire to make near-term policy the purpose of government climate and energy policy now seems to be dividing Labour internally and geographically. However, bridging this divide is proving difficult for government. March’s ‘Green Day’ is emblematic of where the Tories are. First, it was announced as a net zero moment boosting renewable provision. Then it became an energy security day with fossil fuels back to contrast with Labour. It was to be headed by the PM, then it fell the Chancellor, and finally Shapps. In the end, we were left with re-announcements and consultations and no growth plan for either fossil fuels or renewables. To top it off, they repeated the whole thing in July, but again short on any new policy because it's solely designed to be not Labour’s.

Where next

I know what you read this summer. Net zero, despite the column inches happily filled, is not going anywhere. It is not 2013, for one we could only draw the Ashes this year, both parties' caution is born out of a recognition that climate and energy is, and will remain, important to voters. This newsletter will try and cover some of the things driving that and the public opinion behind them. Future editions will look at the grid, hydrogen and the Green Party. Please get in touch if there are others you want to see.

I hope you enjoyed the first Election Energy. Please share with others in case they might too.

Takeaways

The public is more concerned about climate change than ever, and support for action is rising and hardening.

Pro-climate positions have been instrumental to victory in a range of international elections over the past two years, with anti-climate policies harming incumbents.

Energy policy is more symbolic now than previously of how both parties plan to govern with a more interventionst prospective Labour government willing to spend, and Conservatives happy with long-term market signals and short-term politicking.